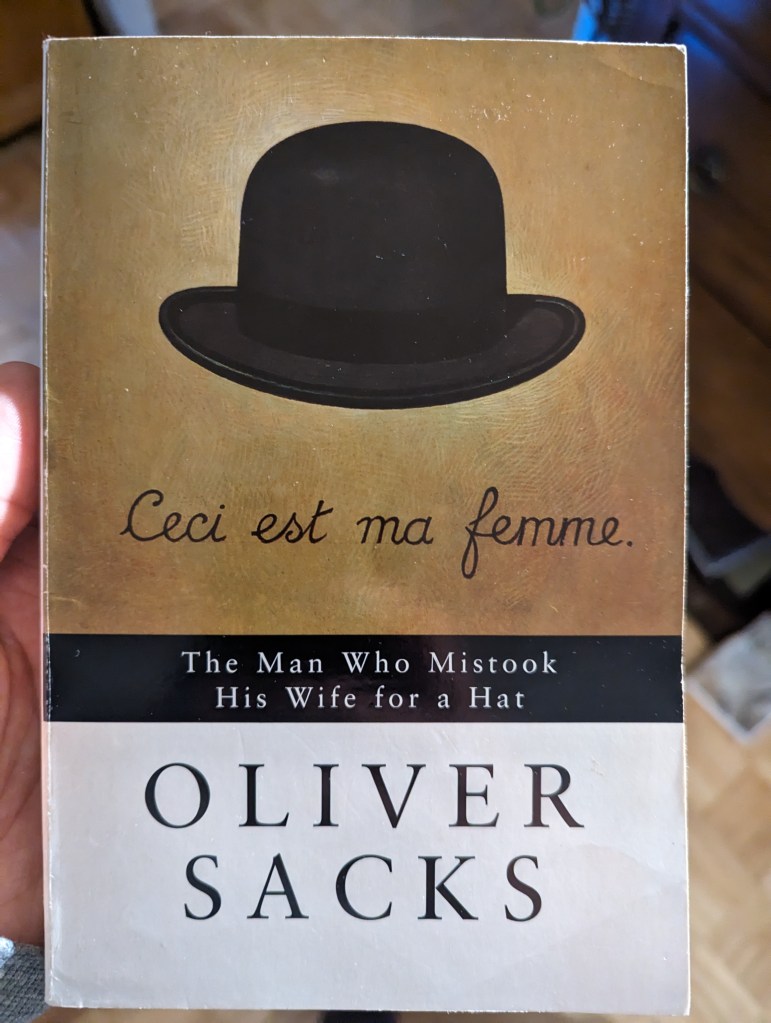

Let’s get one thing out of the gate, the title of this book belongs in the Hall of Fame of Book Titles. And if such a thing does not exist, we’ll have to create it from scratch. It obviously played a role in me buying it, but I had heard of Oliver Sacks beforehand. A well-known British neurologist, he’s written many books about the numerous cases he’s seen in his career. The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat, published in 1985, is one of his first works, where he talks about some of the strangest and most interesting patients he’s seen in those years.

The twenty-four cases are presented as short articles, or essays. They are divided in four parts, Losses, Excesses, Transports and The World of the Simple. In all the cases mentioned in the book, the author gives his professional opinion and goes into the possible causes, the impacts as well as treatments, successful or not, given to the patient.

The first part, Losses, is about patients who are missing something from a neurological standpoint. The eponymous case of the man who mistook his wife for a hat is a good example of this. The patient is an older gentleman who has all the trouble in the world distinguishing objects or things as “wholes”. He will however recognize features or details of those objects. This is diagnosed as visual agnosia. Another patient has seemingly lost every memory from a set date to the present. In other words, he cannot form new memories past that point. The case takes place in the 70s and 80s, yet this poor man still believes he’s back in 1945 when the war ended. He does not realize he’s actually 30 years older, unless he sees himself in the mirror. And even then he’ll soon forget it and continue living his life. It’s incredibly fascinating and sad. The last one I’ll mention here is a lady who has lost her sense of proprioception, and therefore cannot locate her limbs without looking at them.

The second part, Excesses, is quite the opposite. Patients presented here have too much of something. One patient has a charged-up version of Tourette’s syndrome, unable to control the physical urges of his body. This is a well-known disorder but opened Sacks’ eyes to its actual spread in the general population. Another patient is an elderly woman who is suddenly, after her 80th birthday, feeling very frisky and young, flirting with men much younger than she was. Finally, there is the story of a man in a constant state of narrative delirium. He is constantly inventing facts about who he is and who the people he’s talking to are, sometimes changing from one identity to the next multiple times in the same conversation.

The third part is about Transports. The patients here are “transported”, against their will, to other moments or realities and are “living” them. One elderly woman, after having a dream involving music from her childhood, finds that she’s still hallucinating that music quite clearly and loudly while awake. The most remarkable one, to me, is the young man who finds himself waking up with a very strong sense of smell. He went to sleep while under the influence of drugs and dreamt vividly about being a dog. When he woke up, his sense of smell was much, much stronger than a normal human’s, to the point where he could identify many different people by their very distinct smell alone.

The fourth and final part is about what Dr Sacks calls “simple” people, or people with intellectual deficiencies. Here the book shows its age, because the vocabulary used wouldn’t be socially acceptable today (words like “retardates”, “idiots”, etc.). Most of the patients here, while being diagnosed with very low IQ or significant intellectual deficiencies, still show incredible capacities and competencies in a vast array of subjects. One man, while illiterate, has an eidetic memory and can recite the equivalent of a complete musical encyclopedia.

In almost all of the cases mentioned in the book, the author also goes into details about earlier discoveries, studies and books written about specific diagnoses. It helps to have some historical perspective to better grasp our understanding of human mental health issues.

As a book, it manages to be very funny, yet quite sad or disconcerting in other cases. It really drives home our limited understanding of the human brain, even if strides have been made in the past four decades. It’s quite short, barely over 200 pages, and since it’s divided into cases, it can be read piecemeal if your reading periods are short. It’s a great read, plus you’ll get weird looks for people looking at the cover quizzically.

One response to “The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat, by Oliver Sacks”

Génial!!!

LikeLike