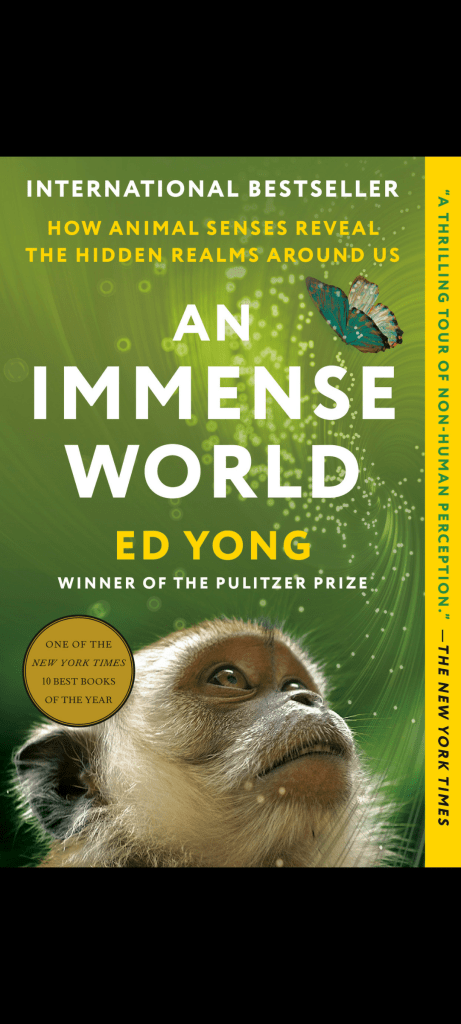

Every so often a book comes along that is so unbelievably interesting that I have absolutely no choice to share it with most people close to me. An Immense World is such a book. I was hooked from the first few sentences and throughout every single chapter. I even took my time reading it because I wanted to make it last as long as possible, therefore going against my – admittedly silly – habit of flying through books as fast as I can.

Ed Yong is a British science journalist of Malaysian descent with incredible writing skills. Unsurprisingly, while still relatively young, he has won multiple journalism awards, including a Pulitzer price for explanatory reporting.

An Immense World focuses on the concept of Umwelt – the German word for “environment” – which can be described as the “self-centered world” of any living organism. It’s how the living organism experiences the world around it according to its particularities, physical characteristics and senses. It’s highly subjective, to the point that two animals living in the exact same environment can have two totally different Umwelten (plural or Umwelt).

At its core, this concept is not as natural as it might appear. It’s really hard, by definition, to try and understand the world with senses we do not possess. Or even, in many cases, with senses that are just highly different from ours. For example, if you’re told that some animals have more cones in their eyes to perceive light and colors, how would you even begin to understand what it means? Sure, you can learn that certain cones catch UV light, but what would that look like? You only frame of reference is yours, I can only describe “colors” with what humans see as colors. It’s a bit unsettling in a way, as if you learned that there were those new, hidden dimensions sharing the same “space” as you are right now.

I honestly feel like I could write a whole book about all the amazing stuff I’ve read in Ed Yong’s work, but I’ll try to stay focused on the essentials. Basically, there are thirteen chapters, each one focusing on a different sense or “way of perceiving” the world an animal might have. There are chemical senses, like smell or taste, and mechanical senses like sight or hearing. However, in some cases, what we humans perceive as a single sense – like sight – can’t be properly analyzed as a single function when discussing the wide variety of the animal kingdom. For each chapter, the author mentions some of the most interesting species in regards to that particular sense.

Senses that seem paranormal to us only appear this way because we are so limited and so painfully unaware of our limitations. Philosophers have long pitied the goldfish in its bowl, unaware of what lies beyond, but our senses create a bowl around us too—one that we generally fail to penetrate.

The first chapter is actually about the chemical senses, smell and taste. In humans, both of these are not perceived as overly useful or even precis, especially when compared to sight and hearing. They seem to vary quite a bit from a person to the next. For certain animals though, they can be of the utmost importance, as they shape how they perceive the world around them. Close to us, dogs come to mind as being especially connected to their sense of smell. For them, as for other animals – like some insects and birds – the amount of information they can gather from odours is staggering, much more than what we usually associate with them as humans.

The variation among possible odorants is so wide that it might as well be infinite. To classify them, scientists use subjective concepts like intensity and pleasantness, which can only be measured by asking people. Even worse, there are no good ways of predicting what a molecule smells like—or even if it smells at all—from its chemical structure.

Sight is split into two chapters. The first one focuses on aspects such as the amount of light that can be processed by eyes, speed (basically frames per second), field of vision in terms of degrees & depth of field. The next chapter is all about colours : UV lights, the width of the visible spectrum, how many cones are in the eye, etc. Here again, there is a such a wide variety of how animals use their ability in regards to their own Umwelt.

Ultraviolet vision is so ubiquitous that much of nature must look different to most other animals. Water scatters UV light, creating an ambient ultraviolet fog, against which fish can more easily see tiny UV-absorbing plankton. Rodents can easily see the dark silhouettes of birds against the UV-rich sky. Reindeer can quickly make out mosses and lichens, which reflect little UV, on a hillside blanketed by UV-reflective snow. I could go on.

Next, we have four chapters that we could all classify under the sense of touch. I think here is a good time to point out that the generally accepted five senses are actually an incomplete way of looking at things. There are nine senses that are widely accepted by the scientific community, and some argue there are up to twenty-one of them. The first two chapters of this bunch are actually about two of those “other” four senses, the perception of pain (nociception) and the perception of heat (thermoception).

Pain (or nociception, if you prefer) is the unwanted sense. It is the only one whose absence (in naked mole-rats or grasshopper mice) feels like a superpower. It is the only one that we try to avoid, that we dull with medication, and that we try to avoid inflicting upon others.

As the quote suggests, pain is different from other senses. When it comes to animals, there are moral issues associated to our interactions with them. Whether it’s for scientific studies or for exploitation – hunting, farming, fishing, etc. – the concept of pain brings about certain questions that some of us might be uncomfortable to face.

Heat plays quite a variety of different roles. For some animals, heat – or the lack thereof – is associated with hibernation. Some squirrels can lower their body temperature to a near-freezing four degrees Celsius when they hibernate, slowing their heart by a factor of more than fifty! Some beetles detect forest fires because they need that very particular ecosystem – a burnt forest – to lay their eggs. Somes species of snakes hunt by infrared heat detection. These are but a few examples of the role of heat for animals in the wild.

Next comes a part of touch that humans excel at, tactile precision. However, we might not be the actual champions of that category, even with our very sensitive hands. Sea otter hold that recognition, with their extremely active and precise paws. For some other animals, touch is not exactly associated with hands or paws. Star-nosed moles, for example, used their eponymous nose to explore and recognize their environment. Certain wasps have extremely precise and sensitive stingers that they use to lay eggs in another insect’s brain. Another well-known organ regarding touch are whiskers, found on so many mammals, including domestic ones like the three cats living in this very house. Other animals in this chapter include manatees, seals, spiders, as well as some reptiles and birds.

The last chapter related – this one less so than the first three – to touch concerns surface vibrations. Amphibian eggs and insects seem to be particularly sensitive to surface vibrations for their survivals, although there are other examples of animals who rely on them on a daily basis.

But vibrations are what really matter. They pass into the eggs and into the embryos, which can distinguish between bad vibes and benign ones without any previous experience of either. A bite from a snake will trigger hatching. Rain, wind, and footsteps will not. Even when a mild earthquake rattled Warkentin’s pond, the embryos didn’t react.

Hearing is the last of the five major senses here. Like touch, it’s a mechanical sense, since sound is simply a vibration that is processed by our ears – or other body parts, depending on the animal. In terms of animal variety, this is probably the most interesting chapter. As the author suggests, the evolutionary paths to hearing are as wildly varied as you can imagine, affecting animals in every possible environment. The main absentees are insects, who are mostly deaf. Other than that, we learn about the abilities of owls, kangaroo rats, túngara frogs, zebra finches, whales, elephants, mice, hummingbirds, and others. As was the case with colors, the humans’ hearing range is limited. We usually use Hertz (vibration per second) as a measure, and the “normal” human range is between 20 and 20 000 Hz. Anything below 20 Hz is considered an infrasound. Anything above is an ultrasound. Whales are the champions when it comes to infrasound, emitting long-range sound as low as 7 Hz that can travel thousands (thousands!!) of miles in the ocean. Ultrasounds, on the other hand, usually travel very short distances.

Fall brings openness: Bare branches make little birds more visible to predators. The ability to localize the sound of approaching danger, which is inextricably linked to fast hearing, becomes paramount. An animal’s Umwelt cannot be static, because an animal’s world isn’t static.

A limited range might be beneficial, however, if animals want to limit their audience. The isolation call of a helpless mouse pup can alert a nearby parent without also alerting more distant predators. In this way, ultrasound really can provide a secret communication channel, not because it lies in an inaccessible frequency range but because it doesn’t travel very far.

After hearing, we delve into something intimately related to that sense : echolocation. Whenever you hear that word, one animal comes to mind first and foremost : bats. They are synonymous with echolocation. And with very good reason, their abilities in that domain are absolutely mind-blowing. I write key words in my notes app on my phone for books I read for the purpose of this blog. To give you an idea of how flabbergasted I was, at some point during this chapter I just wrote “Holy ****” instead of relevant information. The mere fact that bats can actually live and thrive is simply astounding. Obviously there are more animals using echoes as a communication device, like moths and dolphins, but bats take the cake here.

Without vision, the brain can still construct similar maps by repurposing the so-called visual cortex into an echo-processing cortex.

The next two chapters focus on skills and abilities that are beyond our understanding as humans. Not that we can’t explain them or study them, but since they’re absent in us, we can only speculate as to how exactly they “feel”. Some animal can create an electric field (electrogenesis) and some can simply detect it (electroreception). As you can imagine, the vast majority of them live in the water, a fantastic conduit for electricity. It’s mostly used as a communication device by these creatures (catfishes, eels, knifefishes, etc.). Some animals can use it to locate themselves, not unlike echolocation. For some, it can be modulated to fit their needs. Other species, like sharks and rays, cannot generate electricity but they can sense it.

And here’s the part that really baffles me: The fish use the same discharges for navigation and communication. The electric fields they generate to send signals to other fish are the very ones they use when electrolocating.

Finally, there’s the ability to perceive magnetic fields, a sense that has been disputed for a long time, in large part because it’s very hard to study for a few reasons. First, animals do not produce a magnetic field ; they can only sense it. Second, magnetism permeates everything and is affected by nothing, so it’s really hard to pinpoint the organ(s) responsible in any animal. Third, Earth’s magnetic field is very, very weak. Scientists know that animals can sense it, they just don’t know how exactly they do it.

Magnetoreception research has been polluted by fierce rivalries and confusing errors, and the sense itself is famously difficult both to study and to comprehend.

But researchers who study magnetoreception have no such hints. Magnetic fields can pass unimpeded through biological matter, so the cells that detect them—magnetoreceptors—could be anywhere.

Chapter twelve brings all that we’ve learned so far to realize how incredible all of the animals on Earth truly are. While singular abilities have been highlighted over the first eleven chapters, it would be a mistake to think that animals can adequately thrive and survive on the strength of a single sense. The senses come together for the animal to be complete and act within its own Umwelt.

Each sense has pros and cons, and each stimulus is useful in some circumstances and useless in others. That’s why animals tap into as many streams of information as their nervous systems can handle, using the strengths of one sense to compensate for the shortcomings of another. No species uses a single sense to the exclusion of every other. Even animals that are paragons of one sensory domain have several at their disposal.

The thirteenth and final chapter of the book concerns us, how we have shaped the Earth to our own needs while rarely considering what it actually means for the other creatures sharing our planet. It has been said by many experts that we live in the midst of a extinction event spanning the era the humans have exploited the world around them. Obviously, pollution and climate change are immediate threats to the balance of Earth’s ecosystems, but the author goes further. In short, the modern technological advances have made us humans very noisy and very shiny. Our cities are synonymous with noise and light, and that has an impact on animals, even more so if you consider the sheer speed at which all of this has happened over the past century or so. Some animals can adapt over short-ish generations, but for others it’s much harder, or in some cases impossible. It’s certainly a sobering way to end the book, but the message is clear nonetheless.

Instead of stepping into the Umwelten of other animals, we have forced them to live in ours by barraging them with stimuli of our own making. We have filled the night with light, the silence with noise, and the soil and water with unfamiliar molecules. We have distracted animals from what they actually need to sense, drowned out the cues they depend upon, and lured them, like moths to a flame, into sensory traps.

To end what is undoubtedly the longest article I’ve ever written about a book, I’ll keep it simple and state that An Immense World is probably the best non-fiction book I have ever read. The sheer number of “wow” moments I’ve experienced while reading this masterpiece is unequaled. My e-reader tells me I have sixty-six highlights in this book, and I honestly tried to dial it down. I could have had over a hundred. There is just so much information in there that it truly boggles the mind. The animals kingdom has fascinated us for millennia and continues to do so for the younger generation – I can see that first-hand in school – for good reason. Our furry, scaly, feathery, large, minuscule neighbors represent an incalculable source of awe and wonder.

Read this book. You won’t regret it.