Is there a more famous equation in all of science? Even kids have told me lately that E was equal to mc2 (they’ll say the two out loud as “two” and not as “squared” when they are younger) and usually feel like geniuses for even remembering the order of the letters. I probably did that as a kid too. A few science classes in secondary school have allowed me to know, at the very least, that it was the Energy equal to the mass times the speed of light squared. Even then, except for the link between energy and mass, I couldn’t tell you what it meant or why it was multiplied by the speed of light, of all things. I’m fairly sure most of us, if we haven’t studied physics, are in the same boat. Which is probably why the title of this book caught my attention immediately. And please bear in mind that I’m writing this as a physics enthusiast, but certainly not someone with any formal training in the field. If errors have found their way into my understanding and explanations, feel free to correct me.

Unsurprisingly, the authors spend the first few chapters educating the readers on major physics concepts before. At first, they take aim at the notion of absolute time and space, which was the usual way of looking at the world up until a century ago. Then, they tackle the immense work of Faraday and then Maxwell on electricity and magnetism. Ultimately, electricity and magnetism are inextricably linked. Maxwell then realized that electromagnetism traveled as a wave and so did light. He eventually calculated the speed of light at what it known today, approximately 300 millions meters per second.

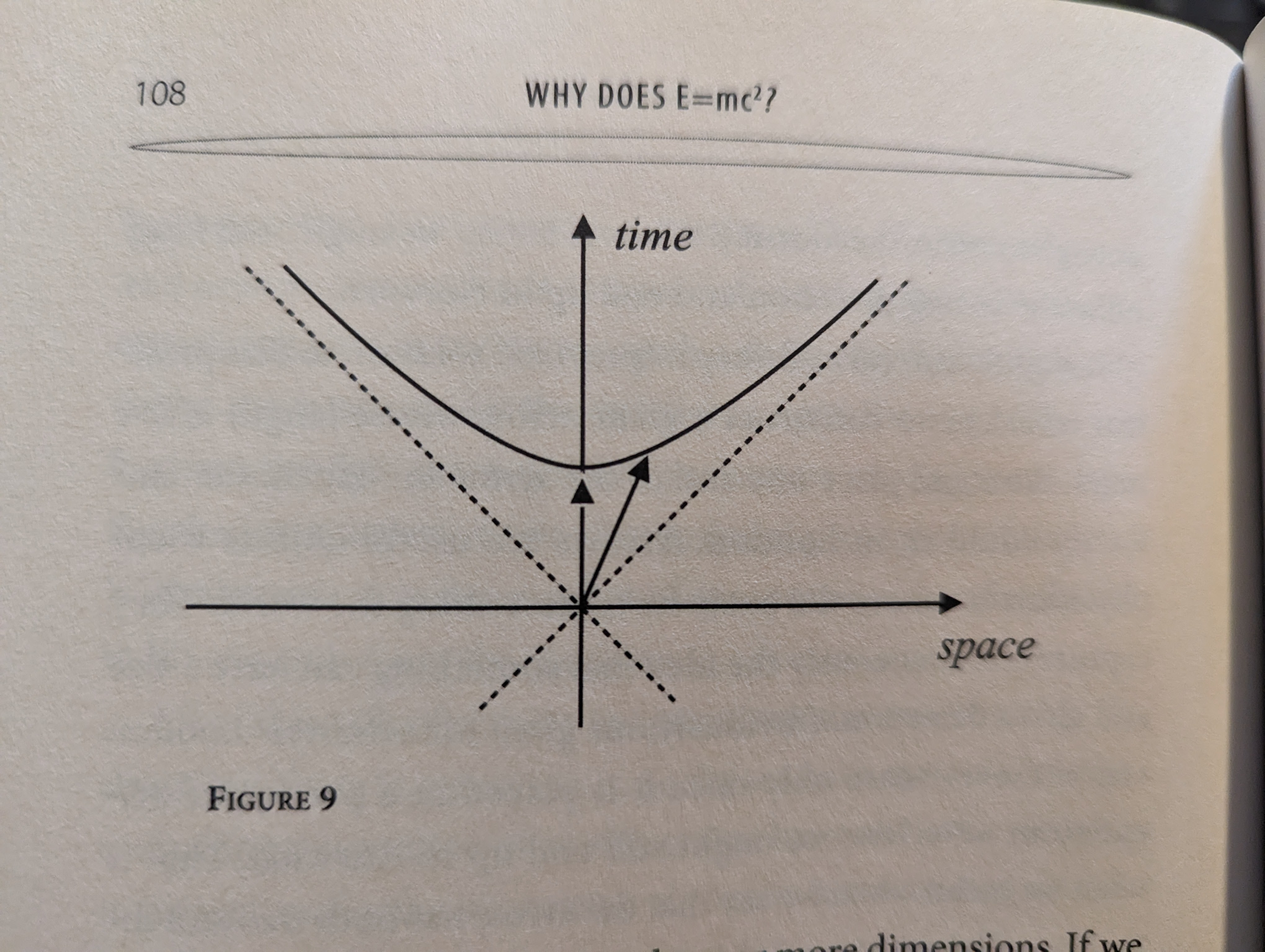

The authors then go on to explain Einstein’s ideas about time and space, and his revolutionary insight that they are not absolute and intrinsically linked to one another. It is what we now call spacetime and it can be, put bluntly, “distorted” under certain circumstances. This idea came in 1905 and is called “special relativity” or “restricted relativity”. In this new – and soon to be verified through experiments – way of understanding the universe, there is a limit (the dotted line on this graph right here) over which the structure of spacetime would “break”. That limit was found to be the speed of light in a vacuum, also known as c.

The next idea leading to the famous equation was the fact that energy and mass were two sides of the same coin. It’s more complex than that, obviously, but that is the general idea. A good way to picture it is with photons, the elementary particle associated with visible light. Photons have no mass, but they carry energy. Therefore, they can have an “effect” similar to mass, as if they had mass. Similarly, objects with mass have an intrinsic energy, even when they are stationary. Obviously the reality in physics terms is much more complicated.

Bringing those two facts together (the speed of light as a limit and the mass-energy equivalence) is how, in short, you get the famous equation. The fact that c, the speed of light, is actually squared in the equation- thus representing an incredibly large number – tells us how much potentiel energy is in matter. Using that energy is incredibly hard though, and even the most advanced technology at the time allowed us to use a tiny fraction at most. In a single kilogram of matter, there it about 89 petajoules of energy, or the equivalent, in combustion terms, of 21.5 megatons of TNT, more than the atomic bombs dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

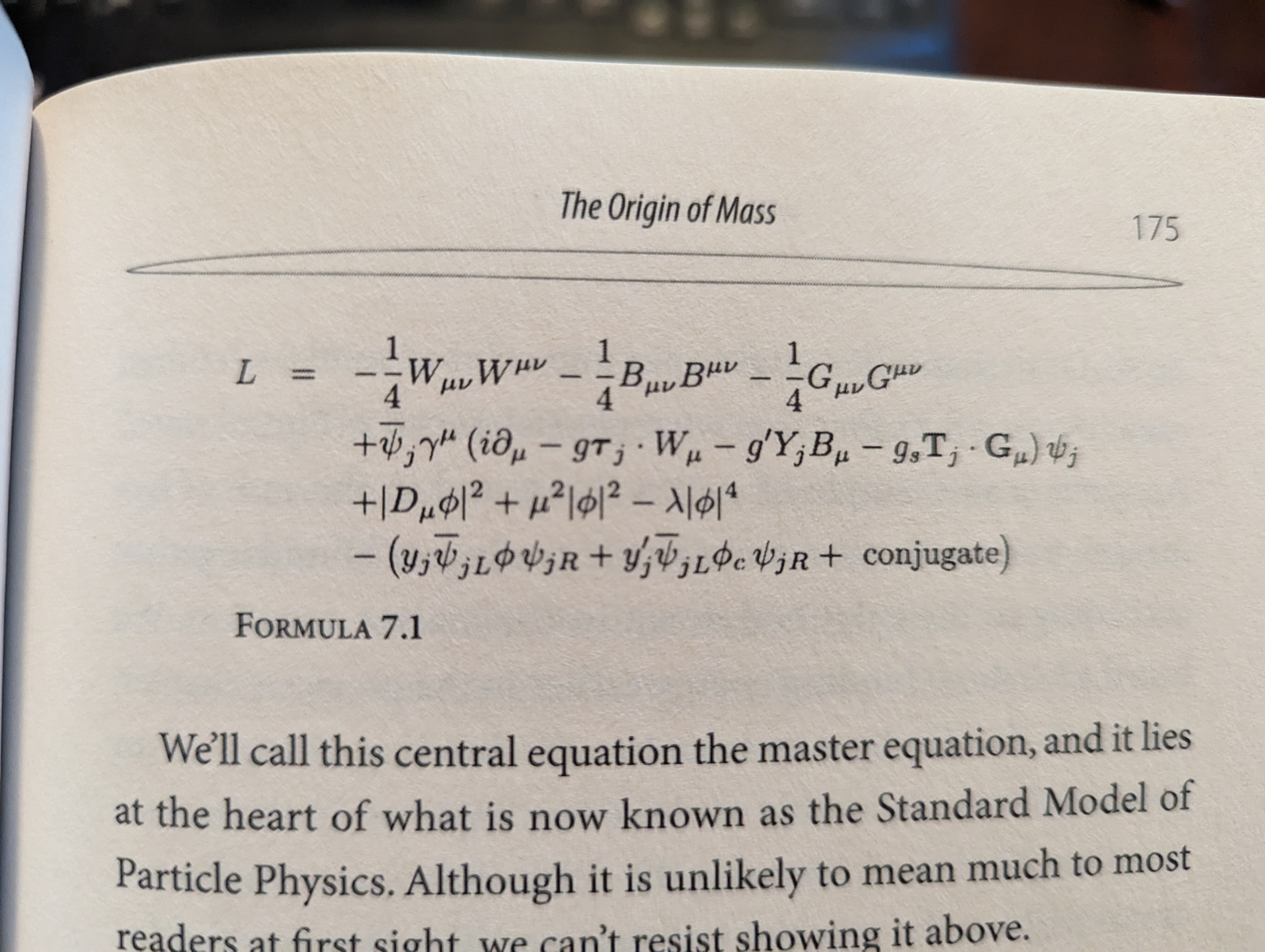

After that part, the authors focus on what exactly does it mean for our understanding of the fundamental laws of physics. There is a bit of math involved, including a massive equation with so many variables it hurts to look at. However, it’s explained in a clear enough way it ends up relatively understandable. I will not pretend I understood all of it, but it’s still staggering to me that such complex concepts can be boiled down to one equation.

The last two chapters are focused on the origins of mass and general relativity. As far as the origins of mass go, we have to bear in mind that this book was written well before the discovery of the Higgs boson in 2013. And for general relativity, they spend the last chapter discussing the numerous experiments that have validated Einstein’s theory over the years as well as its uses in everyday life.

It’s a great book for understanding certain fundamental concepts in physics. The first half in particular was written in a very simple and clear manner, whereas the second half was a bit harder to follow and I had to reread some paragraphs or sections a couple of time to be sure I wasn’t completely lost. Overall, it’s a good book for someone like me with an interest in physics without needing any advanced college course to get the basics.